E. coli in Well Water — Testing, Disinfection, and Long‑Term Protection for Private Wells

If your private well tests positive for E. coli, you’re seeing a red‑flag indicator of fecal contamination. This all‑in‑one guide explains the sources, the health implications, the exact testing steps that minimize false results, the safest way to shock chlorinate, and the proven long‑term solutions like UV disinfection, continuous chlorination, and point‑of‑use reverse osmosis. It’s written in clean, copy‑and‑paste HTML for easy publishing, and includes a practical buyer’s guide with links to watersoftenerplus.com.

AEO‑friendly FAQ + HowTo Schema Single‑file HTML

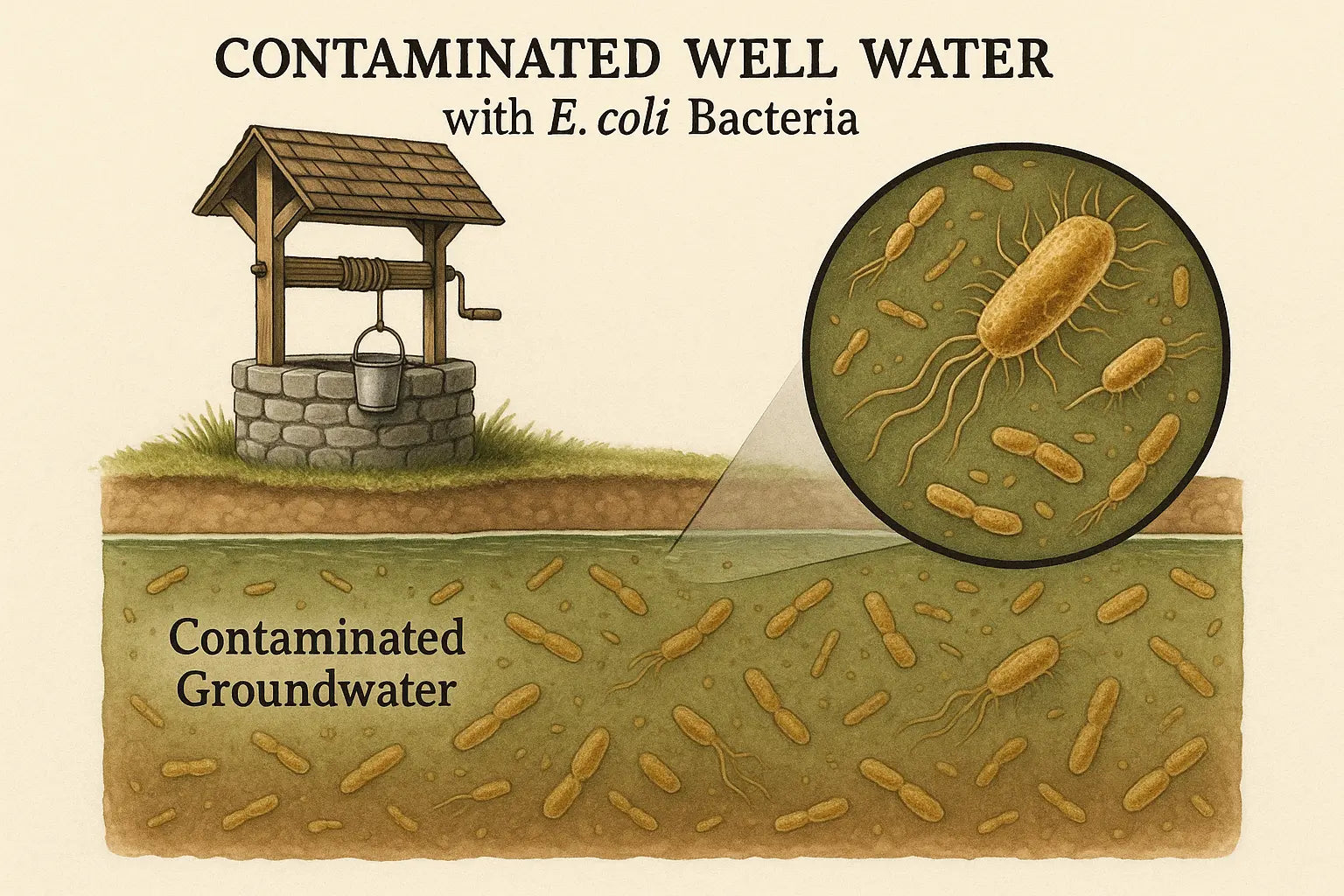

#1) What is E. coli in well water?

Escherichia coli—shortened to E. coli—is a subgroup of fecal coliform bacteria that naturally lives in the intestines of humans and warm‑blooded animals. In the context of drinking water, its detection is a strong indication that fecal material has entered your water supply. Because fecal material can also carry disease‑causing organisms (pathogens) like viruses and protozoa, any presence of E. coli is a do‑not‑drink signal until you remediate the issue and confirm clean results.

Private wells are particularly vulnerable when a surface pathway allows contaminated water to short‑circuit into the aquifer or the well casing. Common culprits include broken or loose well caps, inadequate sanitary seals, compromised grout, pit wells prone to flooding, improper grading that directs surface runoff toward the wellhead, or wells sited too close to septic systems, barns, kennels, or manure storage. Even a well that once tested “clean” can become contaminated after heavy rain or site disturbance, because changing hydrologic conditions can activate new flow paths.

Important context: Public water systems in the United States operate under federal standards that treat any detection of E. coli as an acute health concern, with a health‑based goal of zero. Private wells are not federally regulated, but homeowners should apply the same health‑protective standard in practice. When in doubt, assume the risk is real and act accordingly.

#2) Health risks and who’s most vulnerable

While many strains of E. coli are harmless, some—such as Shiga toxin‑producing E. coli (STEC)—can cause severe gastrointestinal illness. Typical symptoms include abdominal cramps, diarrhea (which can become bloody), nausea, and vomiting. Dehydration can set in quickly, especially in young children and older adults. Rarely, some infections can progress to hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), a serious condition that affects the kidneys and blood. Individuals most at risk include infants, pregnant people, the elderly, and those with weakened immune systems.

Medical note: This article provides general water safety information and home treatment options. It is not medical advice. If you or a family member show severe symptoms (e.g., bloody diarrhea, signs of dehydration, reduced urination, unusual fatigue), seek medical care right away.

#3) Warning signs & situations that increase risk

Events that warrant immediate testing

- Flooding, heavy or prolonged rains, or rapid snowmelt

- Any well service, pump replacement, or plumbing work near the well

- Septic tank overflow, backup, or field failure on your property or adjacent lands

- New construction, trenching, or earthwork uphill of the well

- Changes in taste, odor, or color—especially sudden musty or earthy notes

- Unexplained gastrointestinal illness in household members

Red flags at the wellhead

- Loose, cracked, or missing sanitary well cap

- Electrical conduit gaps or unsealed penetrations

- Casing buried below grade or standing water around the casing

- Downspouts or surface grading directing runoff toward the well

- Proximity to animal pens, manure storage, or barns

- Well located within faulty setback distances to septic tank or field

#4) How to test a private well for E. coli

Testing is the only reliable way to know whether your well is contaminated. You should sample at least once per year for total coliform and E. coli, and more often after risk events. Always use a state‑certified laboratory; they provide sterile bottles, chain‑of‑custody forms, and clear handling instructions. Below is a practical method that aligns with common laboratory guidance.

Sampling steps that reduce false positives/negatives

- Contact a certified lab. Request a bacteria kit for private well owners. Confirm holding time and delivery window.

- Choose the right faucet. Sample from a clean, cold‑water tap closest to the pressure tank. Avoid swivel spouts, hoses, or faucets with sprayers. Remove the aerator if present.

- Disinfect the spout. Wipe the faucet tip with a fresh bleach solution or an alcohol wipe. Allow it to sit briefly.

- Flush the line. Run cold water for 3–5 minutes (or longer for large homes) to draw a representative sample from the well.

- Reduce flow to a gentle stream to avoid splashing that can contaminate the bottle or lose the sodium thiosulfate preservative.

- Open the sterile bottle carefully. Do not touch the inside of the cap or bottle. Fill to the fill line only.

- Cap, label, and chill. Place the bottle on ice or in a fridge (do not freeze) and deliver to the lab within the specified time window.

- Document the conditions. Note weather, recent plumbing work, and any wellhead observations. These details help interpret results.

Which tests should I order?

- Total coliform (presence/absence) — screens the system for contamination pathways or vulnerabilities.

- E. coli (presence/absence, or enumeration) — any presence indicates fecal contamination and requires action.

- Additional parameters as needed — nitrates, iron, manganese, pH, hardness, turbidity, UV transmittance (UVT), and others depending on local geology and land use.

#5) How to read lab results & immediate actions

Private wells are not regulated like municipal systems, but the health‑protective target is the same: zero E. coli. Here’s a simple interpretation framework you can use with your lab report:

| Result | What it means | Recommended action |

|---|---|---|

| Total coliform: Absent E. coli: Absent |

No bacterial indicators detected; your recent sample appears clean. | Maintain routine maintenance and annual testing; keep the wellhead sanitary. |

| Total coliform: Present E. coli: Absent |

System vulnerability or environmental intrusion is likely. | Inspect the wellhead and plumbing; consider shock chlorination; retest to confirm. |

| E. coli: Present | Fecal contamination confirmed—acute health concern. | Do not drink. Use bottled or boiled water. Shock chlorinate, fix sanitary defects, and plan a long‑term barrier. Retest after 7–10 days. |

- Switch to bottled water, or bring water to a rolling boil for 1 minute (3 minutes at high elevations) for drinking, ice, brushing teeth, and food prep.

- Prepare infant formula only with bottled or properly boiled water.

- Plan shock chlorination promptly, then retest in 7–10 days. Persistent positives mean you must find and fix the contamination pathway.

#6) Shock chlorination (step‑by‑step)

Shock chlorination is a short‑term disinfection procedure that treats the well casing, drop pipe, pressure tank, and household plumbing with a strong bleach solution. It is appropriate after floods, well work, or a one‑time positive bacteria test. It does not repair physical defects that allow contamination to re‑enter the system; think of it as a reset button.

Safety prep

- Turn off power at the breaker before removing the sanitary cap.

- Work in a ventilated area; wear eye/skin protection and clothing you don’t mind bleaching.

- Use unscented household bleach (5–9% sodium hypochlorite). Avoid splashless or gel varieties.

- Bypass water softeners and point‑of‑use filters during disinfection to avoid damaging media and cartridges.

Dosage & contact time

- Estimate the water volume in the well (diameter × water column height). Your local health department or lab can help determine the bleach dose; the goal is a strong free chlorine level in the well.

- Mix the calculated bleach with 3–5 gallons of clean water in a bucket.

- Remove the cap and pour the solution into the well. Use a hose connected to an outside spigot to recirculate water back into the well for 15–30 minutes, rinsing the casing and drop pipe.

- Open each tap, one by one, until a chlorine odor is present. Close each tap and move to the next. Don’t forget outdoor taps, showers, and low‑use fixtures.

- Allow a 12–24 hour contact time with minimal water usage.

- Flush to the outdoors first (away from plants, streams, and septic) until the odor fades. Then flush indoors.

- Wait 7–10 days before resampling for total coliform and E. coli.

Tip: If chlorine odor lingers excessively or if you use a septic system, pace your indoor flush to protect drain fields. Carbon filters can help remove residual taste and odor after disinfection.

#7) Find and fix the contamination pathways

Recurrent positives typically mean there’s an unresolved route for contaminated water to enter the system. Inspect the following:

- Sanitary cap & seals: Replace broken or loose caps; seal conduit entries; ensure vermin screens are intact.

- Surface grading: The ground should slope away from the casing. Divert downspouts and surface water.

- Well construction details: Adequate casing height above grade, intact grout, and proper setbacks to septic systems and animal enclosures.

- Septic system health: Pump on schedule; repair leaks; keep heavy vehicles off the field; maintain setbacks for chemical storage and compost.

- Seasonal sources: Spring thaw, heavy rains, or livestock patterns that change runoff quality.

#8) Long‑term treatment: UV, chlorination, RO & filtration

The safest approach combines physical fixes (closing pathways) with a continuous disinfection barrier. Here’s how the common options compare and complement each other.

Option A — Whole‑house UV disinfection (chemical‑free)

- What it does: Inactivates bacteria, viruses, and protozoa at the point of entry. No chemical taste or odor.

- What it needs: Clear water. Keep turbidity low and manage iron/manganese to prevent lamp fouling and shadowing. Choose a model rated for your home’s peak flow.

- Where it fits: Final barrier after sediment/iron treatment and softening (if necessary), just before water branches to the house.

Viqua UV (Whole‑house & POU)

watersoftenerplus.com/collections/viqua-ultraviolet-uv

Broad portfolio from point‑of‑use to high‑flow whole‑house UV. Select by rated GPM and features like sensor/alarm.

UV Water Sterilization, 10 GPM (with prefilters)

watersoftenerplus.com/products/uv-water-sterilization

All‑in‑one kit with sediment and carbon prefilters to protect the UV chamber and quartz sleeve.

Compact POU UV (3 GPM)

watersoftenerplus.com/products/viqua-uv-system

Ideal for a dedicated drinking line or a single bathroom.

Option B — Continuous chlorination + contact time

- What it does: Provides a measurable disinfectant residual throughout the plumbing to control regrowth and protect distribution lines.

- What it needs: Chemical feed pump, solution tank, and a properly sized contact/retention tank. Many homeowners add carbon filtration after chlorination to improve taste.

- Where it fits: A good choice for large homes with long piping runs or recurring bacterial regrowth.

Option C — Point‑of‑use reverse osmosis (RO) at the kitchen

- What it does: Highly effective at polishing drinking water by reducing a wide range of dissolved contaminants. RO membranes provide an additional physical barrier to bacteria.

- Where it fits: Complements whole‑house UV or chlorination by focusing on the tap you drink from most (kitchen/ice maker).

Nelsen 5‑Stage RO (50 GPD)

watersoftenerplus.com/products/nelsen-reverse-osmosis-system-5-stage-50-gallons-per-day

Classic under‑sink system with sediment and carbon prefiltration, an RO membrane, and post‑carbon polish.

Microline Under‑Sink RO

watersoftenerplus.com/products/microline-ro-sys-50-gallons-per-day

Compact footprint for tight cabinets; a smart add‑on beneath the kitchen sink.

Option D — Pretreatment that protects UV and plumbing

Pentek Big Blue 20″ Housing

watersoftenerplus.com/a/p/products/pentek-big-blue-20-filter-1

Large‑capacity cartridge housing for sediment (5–20 µm) or carbon blocks to keep water clear before UV.

Retention Tanks & Sand Trap System

watersoftenerplus.com/products/retention-tanks-and-sand-trap-system

Helps settle heavy particles and oxidized solids ahead of cartridges and UV.

Whole‑House Filter Systems (Overview)

watersoftenerplus.com/pages/whole-house-water-filter-systems

Compare options to build a staged lineup tailored to your well.

#9) Designing a dependable whole‑home setup

A well‑designed system combines right‑sized equipment with clear water quality targets so that each component supports the next. Here’s a proven sequence and the reasoning behind it.

A. Measure your water and your flow

- Water chemistry: turbidity, iron, manganese, hardness, pH, TDS, UV transmittance (UVT), color, and hydrogen sulfide. Use these results to choose pretreatment and decide whether softening is recommended.

- Peak demand (GPM): Count simultaneous fixtures and high‑draw appliances (showers, tubs, laundry). Your disinfection equipment must sustain dose at the highest likely flow.

- Plumbing layout: Identify a clean, dry, serviceable location near the point of entry with an electrical outlet and drain access.

B. A reliable whole‑house sequence

- Coarse solids control — spin‑down or sand trap (if you see grit or heavy particulates).

- Sediment filtration — cartridge or backwashing media to keep turbidity low.

- Optional carbon — for taste/odor and to remove residual chlorine if using chemical disinfection.

- Softening (if hardness > ~7 gpg) — improves plumbing longevity and helps keep the UV sleeve clean.

- UV disinfection — installed last at the point of entry with an intensity sensor/alarm and a normally‑closed solenoid valve.

- POU RO — at the kitchen for drinking and ice; complements the whole‑house barrier with extra polish.

C. Sizing pointers for UV

- Choose a UV rated at or above your peak flow so the dose doesn’t fall below target during showers or laundry.

- Maintain clear water: keep sediment under control and manage iron/manganese. Clean the quartz sleeve per schedule.

- Prefer models with lamp‑on indicators, alarms, and (ideally) intensity monitoring.

#10) Maintenance schedule & record‑keeping

What to do and when

- Monthly: Quick visual check of the well cap, floor drains, and the UV controller. Look for leaks and abnormal noises.

- Quarterly: Replace sediment cartridges (or check pressure drop); inspect the quartz sleeve for fouling.

- Every 9–12 months: Replace standard UV lamps; clean/replace sleeve as required. Log lamp changes.

- Annually: Test total coliform and E. coli; review iron, manganese, hardness, and turbidity; service the softener and carbon media as scheduled.

- After events: Test after floods, heavy rain, well work, or septic issues—regardless of the annual schedule.

How to keep reliable records

- Keep a simple log (spreadsheet or notebook) with dates for lamp changes, filter swaps, media backwash cycles, and test results.

- Note weather events and project work near the well (landscaping, trenching, additions).

- Attach receipts and lab reports; they help troubleshoot and preserve home value.

#11) Seasonal threats: floods, droughts, travel & outages

Hydrologic extremes change how water moves through soil and rock. During floods, water that normally takes months to percolate can short‑circuit into wells within hours, carrying microbes and organic matter that shield them. Drought can concentrate contaminants, and the first heavy storm after a dry spell often flushes a season’s worth of material into surface waters and shallow aquifers. Plan ahead:

- Before storm season: Verify the cap and seals, improve grading, add temporary berms if needed, and stock testing kits.

- After floods: Assume contamination; use bottled/boiled water; shock chlorinate when safe to do so; retest after 7–10 days.

- Power outages: UV systems require electricity. Keep bottled water on hand for outages, or consider backup power if your area experiences frequent blackouts.

- Vacation homes: Stagnant plumbing can harbor regrowth. Flush lines and consider a post‑vacation bacteria test.

#12) Troubleshooting persistent positives

- Re‑evaluate sampling technique: Use a different faucet, flush longer, and disinfect the spout more carefully.

- Inspect the wellhead again: Many issues hide under decorative coverings or landscaping.

- Check pretreatment: Cartridge filters clogged? Iron/manganese fouling the UV sleeve? Replace/clean as needed.

- Verify UV lamp and power: Lamp age, bad ballast, or a fouled sleeve will undermine dose. Confirm indicators and alarms.

- Consider plumbing biofilm: Long dead‑legs or unused fixtures can harbor bacteria. Flush or disinfect those branches.

- Engage a licensed well contractor: If positives persist, you may need a well inspection, pressure test, or grouting repair.

#13) Costs, budgeting, and ROI

Costs vary with water quality, home size, and product features. Here’s a general planning framework:

| Item | Typical cost range (USD) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Annual bacteria test (lab) | $25–$100 | Varies by state/region and test panel. |

| Shock chlorination supplies | $10–$60 | Bleach, bucket, PPE; contractor services cost more. |

| Sediment/carbon pretreatment | $100–$600+ | Cartridges, housings, or backwashing filters. |

| Whole‑house UV system | $300–$1,800+ | Features like intensity sensor, stainless chamber, and high‑flow ratings increase price. |

| Continuous chlorination + contact tank | $600–$2,500+ | Pumps, solution tank, retention tank; add carbon polishing for taste. |

| Under‑sink RO | $200–$700 | Includes faucet and storage tank. |

| Annual UV lamp & sleeve maintenance | $60–$200+ | Per model; sleeves last longer than lamps but still need care. |

Return on investment comes from avoided emergency purchases (bottled water), reduced service calls, and long‑term plumbing protection. For many households, a well‑planned UV + pretreatment + POU RO stack is the sweet spot between reliability and cost.

#14) Mini case studies (real‑world scenarios)

Case 1 — Spring flood, shallow well

After a river over‑topped its banks, a homeowner’s shallow dug well returned positive for E. coli. They switched to bottled water, shock chlorinated, and retested at day 10—still positive. A closer look found a cracked concrete cover and low casing. The fix included raising the casing, installing a sanitary cap, regrading soil, and adding a whole‑house UV with sediment pretreatment. Follow‑up tests were clean three years running.

Case 2 — New baby on the way

A couple expecting their first child had a negative test but wanted redundancy. Their water had 10 gpg hardness with trace iron. They installed a softener, a 20″ Big Blue sediment/carbon stack, and a Class‑A UV system. For the kitchen, they added a 5‑stage under‑sink RO connected to the fridge ice maker. Annual bacteria tests remained negative, and maintenance was straightforward.

Case 3 — Vacation cabin with intermittent use

A lake‑area cabin used monthly showed sporadic total coliform positives (no E. coli). The issue traced to long plumbing branches and infrequently used fixtures. The owners added a periodic flushing routine, replaced old cartridges, and upgraded to a UV with an intensity sensor. They also opened dead‑legs and installed quick‑drain valves. Problem solved.

#15) Glossary

- E. coli

- A fecal coliform bacterium used as an indicator of fecal contamination in water.

- Total coliform

- A broad group of bacteria used to screen water systems for potential contamination pathways.

- Shock chlorination

- A short‑term, high‑dose chlorination process to disinfect a well and household plumbing.

- UV disinfection

- Ultraviolet light used to inactivate bacteria, viruses, and protozoa in clear water.

- Reverse osmosis (RO)

- A membrane process that reduces dissolved salts and many contaminants; typically installed at a single tap.

- UV transmittance (UVT)

- A measure of how well UV light passes through water. High UVT is essential for effective UV disinfection.

- NSF/ANSI 55

- An industry standard for residential UV systems. Class‑A systems are intended for microbiologically unsafe water.

#16) Frequently asked questions

Is there any “safe” amount of E. coli in drinking water?

No. Treat any detection as a do‑not‑drink situation until you correct the source and verify with a clean laboratory test.

How long should I boil water?

Bring water to a rolling boil for 1 minute (3 minutes at higher elevations). Let it cool naturally before storage. Boiling is a temporary measure and does not remove chemical contaminants.

Does a softener remove bacteria?

No. Softeners remove hardness minerals but do not disinfect. Pair with a UV or chlorination barrier.

What if my water looks and tastes fine?

Appearance and taste are not reliable indicators of microbiological safety. Routine testing is essential.

Can I install UV myself?

Many homeowners can, but it requires careful planning, correct orientation, leak‑free plumbing, and electrical access. When in doubt, hire a licensed contractor.

#17) Buyer’s guide (with product links)

Below is a curated list of products from Water Softener Plus to assemble a robust, layered defense against E. coli and other microbes. Match choices to your water quality results and peak flow.

Primary microbial barrier — Whole‑house UV

- Viqua UV Systems (Class‑A & Class‑B) — Choose whole‑house models sized for your GPM; look for intensity monitoring and audible alarms.

- UV Water Sterilization System, 10 GPM (Kit with Prefilters) — Great all‑in‑one starting point.

- Viqua 3 GPM UV (POU) — Dedicated barrier for a single tap or bathroom.

Pretreatment — Keep water clear for UV

- Pentek Big Blue 20″ Housing — Accepts high‑capacity sediment or carbon cartridges.

- Retention Tanks & Sand Trap System — First line of defense against grit and oxidized solids.

- Whole‑House Filter Systems Overview — Compare options to tailor your stack.

Point‑of‑use drinking water polish — RO at the kitchen

- Nelsen RO, 5‑Stage (50 GPD) — Reliable, serviceable classic design.

- Microline Under‑Sink RO — Compact footprint for tight spaces.

- RO Sizing Calculator — Estimate capacity versus your daily demand.

Note: Product availability and model names can change. Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions and local codes.

#18) Printable checklists

Immediate response checklist (positive E. coli result)

- Switch to bottled or properly boiled water for drinking, cooking, ice, and brushing teeth.

- Bypass softeners and filters. Shock chlorinate the well and plumbing.

- Inspect the wellhead, cap, seals, electrical penetrations, and grading.

- Flush and wait 7–10 days, then retest total coliform and E. coli.

- Plan and install a continuous barrier (UV or chlorination). Consider RO at the kitchen.

Annual safety routine

- Test bacteria (total coliform + E. coli) and update your water chemistry panel.

- Service sediment/carbon filters; replace UV lamp; clean the quartz sleeve.

- Check softener salt, settings, and perform a sanitize cycle if recommended.

- Walk the property: maintain setbacks, septic service, and clean well surroundings.

- Update your logbook with maintenance and test results.