Lead Contamination in Well Water: The Complete Homeowner’s Guide (Testing, Treatment & Proven Fixes)

1) Why lead in well water is a big deal

Lead is a potent neurotoxin. In children, even low exposure can harm the brain and nervous system and affect learning, behavior, hearing and growth. Public‑health guidance emphasizes that there is no identified safe blood lead level in children. In parallel, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets the health goal (MCLG) for lead in drinking water at 0 because lead can be harmful even at low exposure; utility compliance for public systems uses a separate “action level” framework, but for a private well the practical target for water you drink is “as close to zero as you can get.”

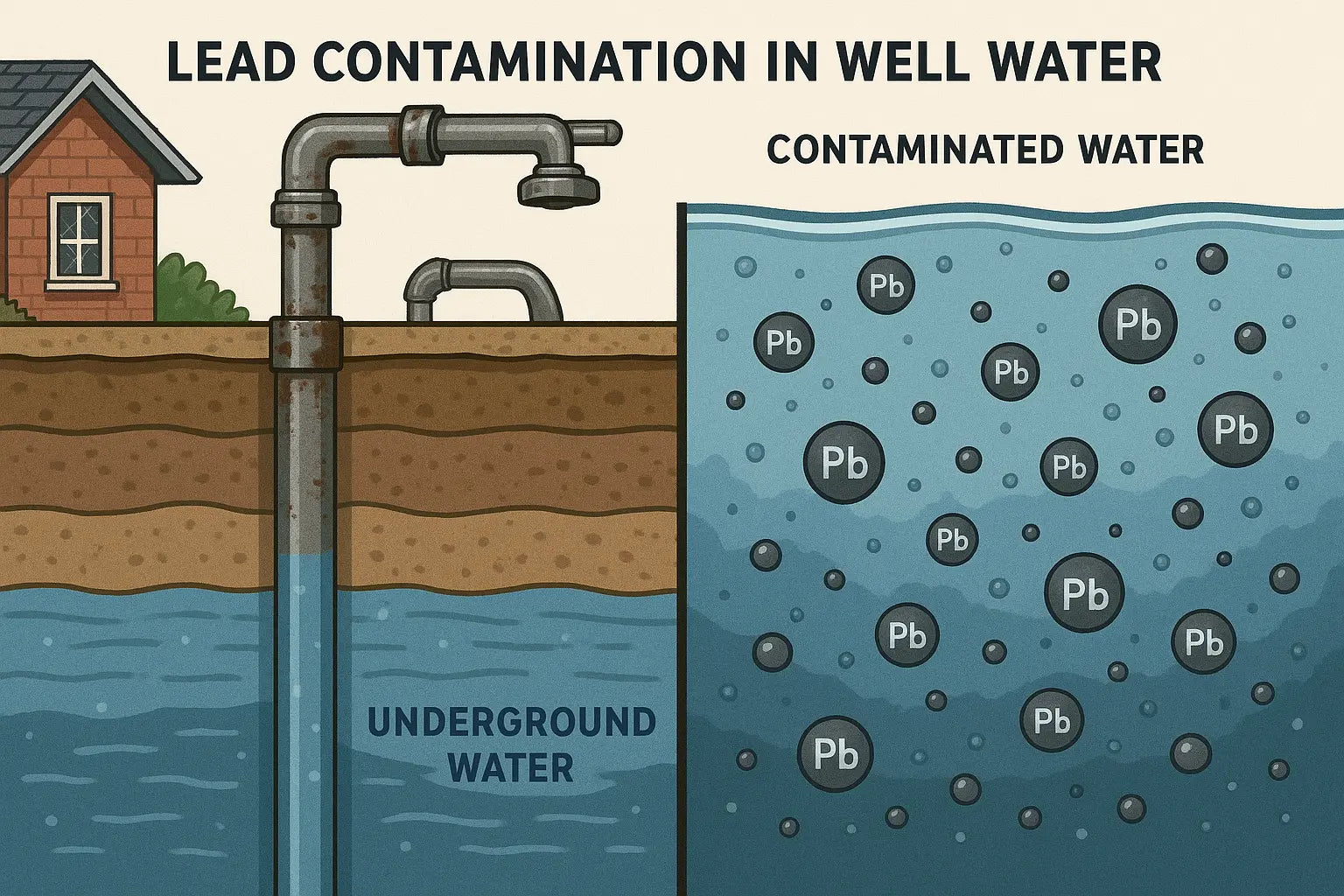

2) How lead actually gets into private wells

Contrary to what many assume, lead usually does not originate in the aquifer. It enters drinking water by corrosion—water dissolving lead from metal parts it touches:

- Household plumbing: older solder, brass fixtures, and some well components.

- Well and pressure tank fittings: any lead‑bearing parts in contact with water.

- Corrosive water chemistry: low pH, low alkalinity, high dissolved oxygen, and other conditions can make water more aggressive toward metals.

Private wells are not federally regulated, and routine monitoring isn’t required by federal law; responsibility for testing and treatment rests with the well owner.

3) Testing 101: getting a true picture of your exposure

A. Use the right sample: first‑draw at the kitchen cold tap

- Collect the very first liter out of the tap after water has sat motionless for at least six hours (overnight works well). Don’t run water beforehand, and don’t remove the aerator for this test. Use the cold tap only. This captures the worst‑case lead level from plumbing contact.

B. When to add flushed or sequential samples

- If your first‑draw sample is high, a flushed sample (after running the tap) can help you compare “stagnation” versus “flowing” conditions.

- Sequential liter samples (collected back‑to‑back without pauses) help pinpoint whether the source is near the faucet or farther back in the plumbing.

C. Also test raw well water

- Collect a sample before any treatment equipment (and ideally before the pressure tank, if possible) to learn whether metals originate before your in‑home plumbing.

D. How often to test

- Test yearly at minimum, and immediately after plumbing changes, when a child under six or a pregnant person moves in, after a period of vacancy, or if water chemistry (pH/alkalinity) changes.

E. Reading results

- Results are typically in µg/L or ppb (parts per billion). While public water systems use a 15 ppb action level, remember the health goal is zero. For a private well supplying your family, any detected lead in the water you drink or use for cooking warrants action.

4) Immediate risk‑reduction steps you can take today

- Use only cold water for drinking, cooking, and infant formula. Hot water dissolves metals faster.

- Flush a stagnant tap before use (run cold water several minutes) if it hasn’t been used for hours. This reduces the portion of water that sat in contact with plumbing.

- Clean faucet aerators (sediment can trap particulate lead).

- Use certified filters at the tap (NSF/ANSI 53 for lead) or a certified RO (NSF/ANSI 58) while you plan a long‑term solution.

These steps don’t replace treatment—they simply reduce near‑term risk.

5) Treatment options that work (with verified product links)

Designing the right solution depends on where lead enters your water and how your family uses water. In many homes, the gold‑standard is a combination: POE lead filtration to protect the whole plumbing system plus POU RO at the kitchen tap for the water you drink and cook with.

A. Whole‑house lead‑reduction (Point‑of‑Entry / POE)

When POE helps most: If first‑draw lead is high throughout the house (multiple sinks), or you want every outlet protected for bathing, brushing teeth, and laundry. Note: A POE filter treats water before it contacts your indoor fixtures; if lead is shed by fixtures downstream of the POE, you’ll still want POU at the drinking tap.

B. Point‑of‑Use (POU) reverse osmosis at the kitchen sink

-

Nelsen 5‑Stage Reverse Osmosis, 50 GPD

-

Quick‑Twist 4‑Stage/Alkaline RO, 75 GPD

-

Ecosoft RObust 1500 RO (high‑capacity)

Why RO at the sink? Lead is often dissolved; RO membranes are specifically evaluated for dissolved contaminant rejection under NSF/ANSI 58. Many “lead” filters are also NSF/ANSI 53 certified for lead reduction (often 0.5‑µm carbon block + adsorptive media) and capture particulate lead as well. Use either approach—but check the certification labeling for lead specifically.

C. Prefiltration and housings (supporting stages)

Good pairing: A 5‑micron sediment filter → catalytic carbon or lead‑reduction cartridge → (optionally) RO at the sink.

D. Microbiological disinfection for private wells (not a lead solution, but often necessary)

UV inactivates microbes; it does not remove lead. Combine UV with the lead‑reduction options above when needed.

6) How to choose the right system for your home

-

Start with test results

- If lead is present only at one or two taps, prioritize POU RO at those taps.

- If lead is detected broadly or you want whole‑home protection, add POE lead filtration.

-

Identify the form of lead

- Dissolved lead → RO or adsorptive media rated for dissolved lead.

- Particulate lead → 0.5‑µm carbon block certified for lead.

-

Check certifications

- Look for NSF/ANSI 53 (lead reduction) and/or NSF/ANSI 58 (RO). The cert must name “lead” explicitly; certification is contaminant‑specific.

-

Match flow and usage

- Whole‑home filters must be sized to your peak flow (showers, laundry, dishwasher at once). At the sink, choose RO GPD capacity to match daily cooking and drinking needs.

-

Plan maintenance from day one

- Put filter changes on a calendar and re‑test post‑treatment water at least annually—and any time parts are replaced.

7) Installation & maintenance checklists

POE (whole‑house) lead filtration

- Install before the water branches to the house but after the pressure tank (to avoid pump short‑cycling).

- Add sediment pre‑filtration (5 µm) upstream to protect your lead cartridge.

- If you also need UV, order is: sediment → carbon/lead media → UV.

- Bypass valves on both sides for easy service.

- Keep spare cartridges on hand; note pressure‑drop increase as a signal for changeout.

- Record install date and set reminders at manufacturer’s recommended capacity/intervals.

POU RO at the sink

- Verify feed pressure and TDS are within the membrane’s spec.

- Use a dedicated faucet; run a line to the fridge if desired.

- Replace pre/post filters every 6–12 months; membrane every 24–36 months (usage dependent).

- Sanitize housings during filter changes.

- Re‑test for lead at the RO faucet after any service.

Re‑testing plan

- First‑draw sample at kitchen after install.

- Optional flushed sample for day‑to‑day exposure comparison.

- Annual check or sooner if water taste/odor changes or plumbing work occurs.

8) Real‑world scenarios & what to install

Scenario A: Older brass fixtures; acidic well water (pH ~6.3); first‑draw 12 ppb at two sinks.

Goal: Whole‑home protection + best drinking water.

Solution: LeadSafePlus POE at the main + Nelsen 5‑Stage RO at kitchen. Retest.

Scenario B: New build with “lead‑free” plumbing; first‑draw <5 ppb at kitchen, not detected elsewhere.

Goal: Extra safety for infants/toddlers.

Solution: Install Quick‑Twist 75‑GPD RO at kitchen for the water you drink and use for formula; periodic first‑draw checks.

Scenario C: Farm well with iron and intermittent coliform; first‑draw lead detected at 7 ppb.

Goal: Address metals + microbes.

Solution: Sediment → PureStreamX POE → VIQUA UV → RO at kitchen. Iron pretreatment extends carbon/media life; UV protects against bacteria; RO ensures near‑zero at tap. Retest.

9) Common mistakes to avoid

- Confusing water softening with lead removal. Softeners exchange hardness minerals; they don’t remove lead for health protection. Pair a softener with RO/lead‑rated filtration when needed.

- Sampling the wrong way. Running the tap before sampling or using hot water will under‑ or misrepresent exposure. Use first‑draw, cold water, 6‑hour stagnation.

- Ignoring certifications. “NSF certified” means little unless the specific contaminant (lead) and the right standard (53 or 58) are listed.

- Skipping re‑testing. Filters are not “set and forget.” Re‑test post‑treatment water on a schedule.

10) Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Are private wells regulated like city water?

A: No. Private wells aren’t regulated under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act; homeowners are responsible for testing and treatment.

Q: If the EPA action level is 15 ppb, why aim for zero?

A: The MCLG health goal is 0. Action levels are a public‑system compliance tool, not a “safe” threshold for your household. For family health—especially with kids—strive for as low as achievable at the tap you drink from.

Q: My state map shows corrosive groundwater. Does that mean I have lead?

A: Not necessarily. Corrosive water can leach lead if it encounters lead‑bearing plumbing. If your system has no leaded materials, you may still test low. But the only way to know is to test.

Q: Carbon filter or RO—what’s better for lead?

A: Both can be excellent if certified for lead. Many whole‑house systems use adsorptive/carbon media (NSF/ANSI 53 claim for lead) to cut soluble and particulate lead. RO (NSF/ANSI 58) is outstanding for dissolved lead and broader dissolved contaminants at the drinking tap. Ideally use POE + POU together.

Q: How exactly do I collect a correct sample?

A: Use a first‑draw liter from the cold tap after ≥6 hours with no water use; don’t remove the aerator for that test. For diagnostics, add flushed or sequential samples if needed.

11) Verified product links (quick list)

- LeadSafePlus – Whole‑House Lead Removal System

- PureStreamX Whole‑House Lead Water Filter

- Nelsen 5‑Stage RO, 50 GPD (Under‑Sink)

- Quick‑Twist / Alkaline RO, 75 GPD (Under‑Sink)

- Ecosoft RObust 1500 RO (High Capacity)

- Pentek Big Blue Housings & Cartridges (1″, 10″)

- VIQUA Whole‑Home UV (12 GPM)

- VIQUA 3 GPM UV (POU)

A practical, step‑by‑step plan you can follow this week

Day 1–2: Order testing + short‑term protection

- Arrange a first‑draw lead test for the kitchen cold tap, plus a raw well sample.

- While you wait, use a certified lead‑reduction filter at the tap or bottled water for drinking and infant formula.

Day 3–4: Map results to solutions

- Lead detected at kitchen only: install POU RO (e.g., 5‑stage under‑sink system).

- Lead detected broadly: add POE lead filtration at the main, and still keep POU RO for drinking and cooking.

Day 5: Installation

- Install pre‑filtration and your chosen POE/POU units (see checklists above).

- If coliforms were detected, add UV after filtration.

Day 6–7: Verify performance

- After any filter run‑in/flush, re‑test the RO faucet and one other tap. Keep results in your household water log.

Final notes & disclaimers

- This guide is for educational purposes and is not medical advice.

- Always follow your product’s manual and verify certifications (look for “lead” on the certification sheet).

- If a child or pregnant person may have been exposed, talk to a healthcare professional about blood lead testing.