Well Water • Pathogen Contaminations • Bacteria

Pseudomonas in Well Water: A Complete Homeowner’s Guide to Risks, Testing & Treatment

If your water test flagged Pseudomonas—or you’re noticing recurrent slime in aerators, cloudy ice, or stubborn odors—this all‑in‑one guide explains what it means, how to test correctly, how to disinfect the well and plumbing, and how to keep bacteria away with proven whole‑house and point‑of‑use solutions.

Table of Contents

- What is Pseudomonas?

- Why it matters in private wells

- Signs and symptoms vs. other bacteria

- How it gets into wells and plumbing

- Testing: sampling, what to order, interpreting results

- Immediate steps after a positive test

- Shock chlorination: homeowner overview

- Permanent barriers: UV and continuous chlorination

- Point‑of‑use polishing (RO, microbiological purifiers)

- Long‑term prevention & maintenance

- Sizing & selection cheat‑sheet

- Troubleshooting & common pitfalls

- Product picks (with links)

- FAQs

- Glossary

- Disclaimer

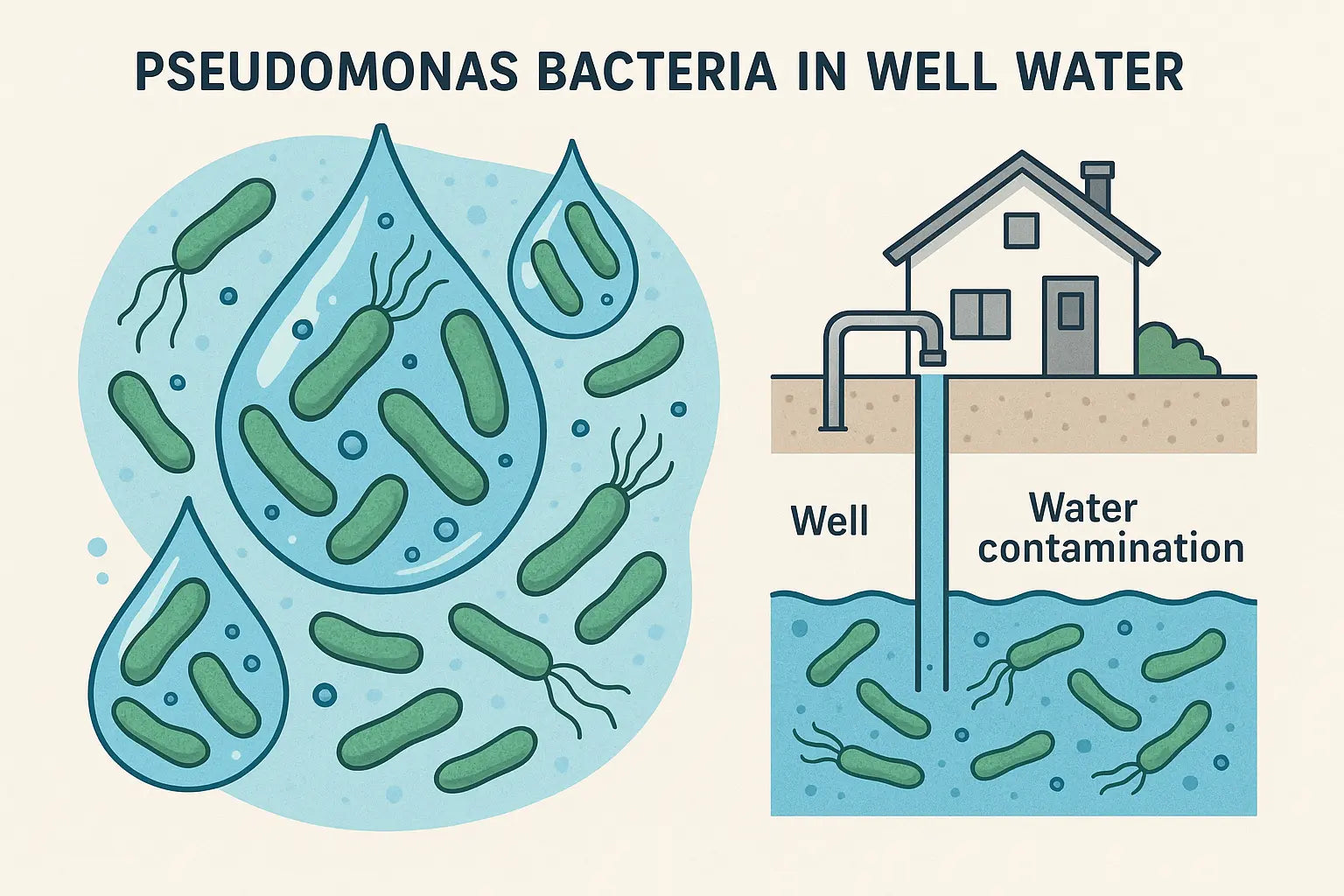

What is Pseudomonas?

Pseudomonas is a genus of bacteria found widely in soil, surface water, and damp environments. The species most often discussed in water hygiene is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a hardy, adaptable organism that thrives in low‑nutrient conditions and forms protective biofilms on plumbing surfaces. Unlike classic fecal‑oral pathogens (which typically cause illness via ingestion), Pseudomonas is considered an opportunistic pathogen: it poses a higher risk when it meets vulnerable hosts (e.g., open wounds, indwelling medical devices, immunocompromised individuals) or poorly maintained plumbing where it can persist.

Why it loves plumbing

- Biofilm formation: it adheres to pipe walls, filter media, and aerators, creating a protective community that resists flushing and intermittent disinfectant exposure.

- Stagnation tolerance: it flourishes where water sits—unused guest baths, oversized lines, and storage tanks with low turnover.

- Low nutrient needs: even tiny amounts of organic matter (from scale, corrosion by‑products, or filter media) can support growth.

- Disinfectant tolerance in biofilms: once established, surface‑attached communities can be more tolerant than free‑floating cells.

Finding Pseudomonas in a private well is a practical red flag about system hygiene and barriers rather than a one‑time “bad sip.” The right response is to clean, disinfect, verify via testing, and then maintain a steady barrier going forward.

Why Pseudomonas in well water matters

Even if healthy adults are unlikely to get sick from a single glass of water that happens to contain Pseudomonas, its presence signals that your system can support biofilm colonization. That matters for several reasons:

- Vulnerable household members: higher caution for individuals with wounds, medical devices, chronic conditions, or weakened immune systems.

- Persistent nuisance issues: cloudy ice, recurring slime in aerators, and odors often track back to biofilms.

- Maintenance signal: it usually means the wellhead, plumbing, or treatment hardware needs attention.

Signs & symptoms in the home (and how they differ from other bacteria)

| Observation | Often associated with | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Slime in aerators/showerheads | Pseudomonas, general biofilm, iron bacteria | Remove aerators, descale, and sanitize. Treat root cause (stagnation and lack of residual/barrier). |

| Greenish/blue stains | Copper corrosion | Usually not microbial. Check pH and corrosivity. |

| Metallic/sulfur odors | Iron or sulfur bacteria; hydrogen sulfide | Not specific to Pseudomonas. Pre-oxidation and carbon or anode rod changes may be needed. |

| Cloudy ice or fast filter clogging | High particulates, biofilm shedding | Check sediment prefiltering and replace on schedule; sanitize housings. |

No single “look” confirms Pseudomonas. A lab test is the only reliable way to know.

How Pseudomonas gets into your well and plumbing

- Surface intrusion at the wellhead: worn seals, cracked caps, poor grading, or floodwater can carry microbes to the well casing.

- Construction & service work: pump pulls and plumbing work performed without proper sanitization can introduce bacteria.

- Stagnant plumbing sections: guest baths, seasonal homes, oversized storage, and long branch lines invite biofilms.

- Spent filters: exhausted carbon or sediment cartridges can become microbial harbors if not changed and sanitized.

- Loss of disinfectant residual: continuous chlorination that runs out of solution or drifts low can allow rebound.

Once inside, Pseudomonas adheres to surfaces and establishes biofilms that are tough to remove unless you address the whole system—source, plumbing, and treatment equipment.

Testing: what to order, how to sample, how to interpret

What to order from a certified lab

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa presence/absence or enumeration (as offered by your lab).

- Total Coliform and E. coli (sanitary indicators).

- HPC (heterotrophic plate count) to gauge regrowth potential.

- Optional: broader “opportunistic pathogens” panel if advised by your clinician or local health authority.

How to collect a representative sample

- Clarify the question: sample the raw water from a pre‑treatment port if you’re assessing the well; sample a treated kitchen tap if you’re assessing what you drink. Taking both is ideal.

- Use sterile bottles supplied by the lab. Remove aerators, sanitize the faucet tip, run water to stabilize temperature, and avoid touching the cap or bottle lip.

- Ship cold with the lab’s chain‑of‑custody. Follow timing instructions.

Interpreting typical results

- Pseudomonas not detected: good news—focus maintenance on preventing biofilms and keep your barrier in place.

- Pseudomonas detected: treat as a system hygiene issue; move to immediate precautions and remediation below.

- Elevated HPC with nuisance slime: suggests conditions that support regrowth; check stagnation and residuals.

Immediate steps after a positive result

- Use boiled or bottled water for consumption: bring water to a rolling boil for at least one minute (three minutes at high altitude). Use for drinking, cooking, brushing teeth, and making ice.

- Protect wounds, contact lenses, and medical devices from tap water; use sterile or boiled water and follow clinical guidance.

- Clean fixtures: remove aerators and showerheads, descale with vinegar, and sanitize with dilute, unscented bleach; rinse thoroughly.

- Replace or bypass spent filters and sanitize housings.

- Plan remediation: shock chlorinate, flush, and retest; then add a permanent barrier (UV or continuous chlorination) with proper pretreatment.

Shock chlorination: homeowner overview

Shock chlorination is a one‑time, high‑dose disinfection of the entire system—well casing, pump, pressure tank, hot and cold plumbing, and fixtures. It is the standard first response to a bacteria detection in a private well.

Key principles

- Calculate dose properly: the amount of bleach depends on well diameter, water column height, and system volume. When in doubt, consult local health department tables or a licensed well contractor.

- Use unscented household bleach (no additives). Wear eye/skin protection and ensure ventilation.

- Mix and circulate: introduce bleach, recirculate to the well, and pull chlorinated water to each fixture until chlorine odor is detectable.

- Allow adequate contact time: many procedures recommend leaving the system overnight.

- Flush to waste carefully: avoid discharging strong chlorine to septic tanks; use an exterior hose bib to discharge to gravel or lawn as permitted.

- Retest 1–2 weeks after shock and again after installing a permanent barrier.

Permanent barriers that work: UV disinfection and continuous chlorination

Whole‑house UV disinfection

Ultraviolet systems inactivate bacteria and other microbes as water passes a UV lamp inside a quartz sleeve. UV is chemical‑free, fast, and highly effective—if the water is clear and pretreated.

- Pretreatment matters: sediment (5 μm), iron/manganese control, and adequate UV transmittance (UVT) protect performance.

- Maintenance: replace lamps annually and clean or replace the quartz sleeve as directed; monitor alarms and flow rates.

- Scope: UV protects the whole house at the point‑of‑entry (POE) but does not leave a residual in downstream plumbing.

Continuous chlorination + contact tank

Metering a controlled dose of chlorine into the water stream creates a residual that persists through plumbing and storage, helping to suppress regrowth between uses. A contact tank provides the detention time needed; a carbon filter after the contact tank removes chlorine taste and odor for the whole home.

- Set a target residual: enough to protect, not so high that it causes taste issues downstream of carbon.

- Maintain solution strength and pump calibration so the residual stays consistent year‑round.

- Combine with carbon and sediment filtration for great‑tasting water.

| Method | Strengths | Watch‑outs | Best fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV (POE) | Chemical‑free, instant inactivation, excellent for bacteria when pretreated properly. | Needs clear water; lamp/sleeve maintenance; no residual in plumbing. | Homes wanting chemical‑free disinfection with solid pretreatment and straightforward plumbing. |

| Continuous chlorination | Provides protective residual in plumbing and storage; helps with complex layouts and long branches. | Taste/odor unless followed by carbon; requires chemical handling and routine monitoring. | Seasonal homes, properties with storage tanks, or systems prone to regrowth. |

| Both together | Redundancy: UV for immediate inactivation + low‑level residual for distribution piping. | Higher cost and maintenance, but robust protection. | Households prioritizing maximum resilience (e.g., vulnerable users). |

Point‑of‑use polishing at the kitchen tap

Even with whole‑home treatment, many homeowners add kitchen‑sink polishing for extra assurance and taste.

- Reverse Osmosis (RO): excellent for dissolved salts and many contaminants. Standard RO is not a primary microbial barrier, so pair it with upstream UV or choose a purifier tested for microbial reductions if that claim is needed.

- Microbiological purifiers / ultrafilters: some faucet‑level systems are tested for bacteria/virus/cyst reduction; follow cartridge replacement schedules and sanitize during changes.

- Faucet‑level UV: compact units provide on‑tap disinfection where whole‑house upgrades aren’t feasible.

Long‑term prevention and maintenance

Protect the wellhead

- Use a vermin‑proof sealed cap; inspect annually for cracks and gasket wear.

- Ensure positive grading so surface water drains away from the casing; keep the top 12–18 inches above grade.

- Maintain a clean zone around the well (50–100 ft): no manure piles, kennels, or chemical storage.

- Seal penetrations with appropriate materials; repair damaged casing promptly.

Plumbing hygiene

- Reduce stagnation: flush seldom‑used fixtures weekly; consider auto‑flush timers for dead‑end branches.

- Replace cartridges on time and sanitize housings at every change.

- Descale & sanitize fixtures (aerators, showerheads) quarterly.

- Water heater care: maintain safe setpoints and flush sediment to reduce biofilm niches.

- Stay on top of your barrier: UV lamp and sleeve maintenance or chlorinator residual checks should be scheduled and logged.

Sizing & selection cheat‑sheet

Right‑sizing equipment avoids nuisance alarms and ensures you get the protection you paid for.

1) Know your peak flow (GPM)

Estimate by counting simultaneous uses (e.g., two showers + dishwasher). Match UV flow rating to this peak. Oversizing a bit is okay; undersizing is not.

2) Test the water chemistry

- Sediment/turbidity: plan a 5 μm prefilter; go finer if needed but watch pressure drop.

- Iron/manganese: remove or reduce to protect UV clarity and prevent staining.

- UV Transmittance (UVT): clearer water = better UV performance.

3) For chlorination systems

- Size a contact tank to provide adequate contact time for the target residual.

- Include a granular activated carbon unit after the contact tank for great taste.

- Set up a test kit routine (free chlorine at nearest and farthest taps).

4) Point‑of‑use polishing

- Standard NSF/ANSI 58 RO for polishing; consider adding a downstream UV or a purifier tested for microbial reduction if required.

- Replace post‑filters on schedule; sanitize the RO tank annually.

Troubleshooting and common pitfalls

- “I shocked the well but results bounced back.” Biofilms in plumbing may have survived; repeat shock with better mixing/contact time, then add a permanent barrier, and sanitize fixtures and filters.

- “UV is alarming.” Check lamp age, sleeve cleanliness, and flow; verify prefilters aren’t clogged; confirm iron/manganese removal is working.

- “Chlorine taste.” Verify carbon post‑filter condition and correct bypass settings; ensure you’re not over‑dosing the feed pump.

- “Filters slime up fast.” Increase change frequency, sanitize housings, and address upstream stagnation or residual loss.

- “Seasonal home issues.” Flush lines on arrival; consider a continuous residual or UV that stays powered year‑round (with freeze protection as needed).

Recommended product categories (with links)

Choose models sized for your flow rates and water chemistry. When in doubt, share your lab report and peak flow estimate with product support for sizing help.

- Whole‑House UV Disinfection — chemical‑free inactivation when water is properly pretreated.

- Continuous Chlorination + Contact Tanks — adds a protective residual throughout plumbing.

- Whole‑House Carbon Post‑Filters — great taste after chlorination; also helps with odors.

- Sediment Prefilters (5 μm) — essential upstream of UV and RO.

- Iron & Manganese Filters — improve clarity, protect equipment, reduce staining.

- Under‑Sink Reverse Osmosis — polished drinking water at the tap.

- Microbiological Purifiers / Ultrafilters — faucet‑level defense for vulnerable users.

- Well Disinfection Kits — supplies for shock chlorination and system sanitization.

Printable checklists

Remediation sequence

- Switch to boiled or bottled water for consumption.

- Clean and sanitize aerators, showerheads, and filter housings.

- Shock chlorinate the well and entire plumbing; allow contact time; flush to waste.

- Retest 1–2 weeks later; if clean, install your permanent barrier.

- Install UV (with pretreatment) or continuous chlorination + contact tank; add carbon for taste as needed.

- Document results; schedule regular maintenance and seasonal checks.

Quarterly prevention

- Walk the wellhead; verify the cap and sanitary seal; keep the area cleared.

- Exercise seldom‑used taps; flush branch lines; descale and sanitize fixtures.

- Replace filter cartridges on schedule; sanitize housings every change.

- For UV: confirm lamp hours; clean sleeve; check flow and alarms.

- For chlorination: verify solution strength and pump calibration; spot‑check residuals at near and far taps.

Frequently asked questions

Is it safe to shower if my well has Pseudomonas?

For most healthy people, showering is typically low risk if water isn’t swallowed and there are no open wounds. Vulnerable individuals should take extra precautions and consult healthcare providers.

How long should I boil water?

Bring water to a rolling boil for at least one minute (three minutes above ~6,500 ft). Let it cool before use and store in clean, covered containers.

Will one shock chlorination fix the problem forever?

No. Shock is a reset, not a permanent solution. Add a whole‑home barrier (UV or chlorination) and keep up with maintenance to prevent recurrence.

UV or chlorination—which is better?

UV is chemical‑free and highly effective when water is clear. Chlorination provides a protective residual in plumbing and storage. Many homes use both: UV for immediate inactivation plus a low residual for complex plumbing.

Can I rely on a water softener for bacteria?

No. Softeners remove hardness minerals; they do not disinfect. Pair your softener with UV or chlorination if bacteria are present.

How often should I retest?

After shock, retest in 1–2 weeks. After installing the barrier, verify performance with a follow‑up test. Then include bacteria checks in your seasonal or semi‑annual testing, or sooner if symptoms return.

Glossary (quick definitions)

Biofilm a surface‑attached community of microbes that resists flushing and intermittent disinfectants.

HPC heterotrophic plate count—an indicator of general bacterial regrowth potential (not a fecal indicator).

POE point‑of‑entry—whole‑house treatment location (where water enters the building).

POU point‑of‑use—treatment at a single fixture (e.g., kitchen tap).

Residual a measurable amount of disinfectant left in water that continues to protect downstream plumbing.

UVT UV transmittance—a measure of how transparent water is to UV light; higher is better for UV systems.

Important disclaimer

This article provides homeowner education and planning guidance. It is not a substitute for local code requirements, professional well service, or medical advice. If anyone in your home is immunocompromised or has special medical needs, consult their care team for water‑use precautions. When handling disinfectants, follow all label and safety directions. If you are unsure about any step, hire a qualified well contractor.